StudentShare

Our website is a unique platform where students can share their papers in a matter of giving an example of the work to be done. If you find papers

matching your topic, you may use them only as an example of work. This is 100% legal. You may not submit downloaded papers as your own, that is cheating. Also you

should remember, that this work was alredy submitted once by a student who originally wrote it.

Login

Create an Account

The service is 100% legal

- Home

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services

- Extra Tools

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us

✕

- Studentshare

- Subjects

- Law

- Was the Secession of the Republic of South Sudan from the Republic of Sudan Doomed

Free

Was the Secession of the Republic of South Sudan from the Republic of Sudan Doomed - Research Paper Example

Summary

"Was the Secession of the Republic of South Sudan from the Republic of Sudan Doomed" paper examines the role of oil and oil agreements in the secession of South Sudan from the Republic of South Sudan. It considers the role of oil initially in the civil war with the comprehensive peace agreement…

Download full paper File format: .doc, available for editing

GRAB THE BEST PAPER91.6% of users find it useful

- Subject: Law

- Type: Research Paper

- Level: Undergraduate

- Pages: 17 (4250 words)

- Downloads: 0

- Author: omarks

Extract of sample "Was the Secession of the Republic of South Sudan from the Republic of Sudan Doomed"

WAS THE SECESSION OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FROM THE REPUBLIC OF SUDAN DOOMED? By name

City, State

Date

Table of Content

Table of Content 2

Table of Abbreviations 3

1.0 Introduction 5

2.0 Methodology 7

3.0 Results/Findings 7

3.1 Background 7

3.2 Oil Issues in Secession Negotiations 9

3.3 Discrepancies in oil revenue sharing 11

3.4 Explanations of oil production discrepancies 14

3.5 Overview of Petroleum Regime in the Republic of South Sudan 16

4.0 Conclusion 18

Reference List 19

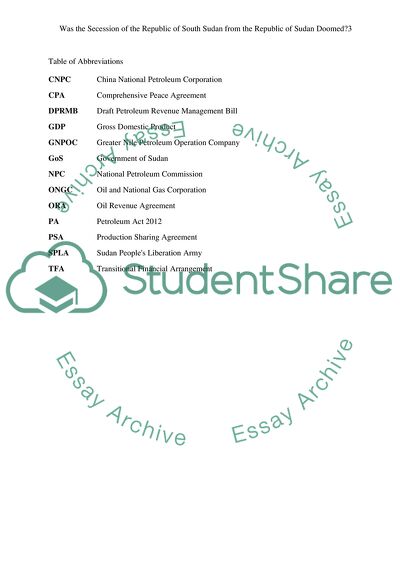

Table of Abbreviations

CNPC China National Petroleum Corporation

CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement

DPRMB Draft Petroleum Revenue Management Bill

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GNPOC Greater Nile Petroleum Operation Company

GoS Government of Sudan

NPC National Petroleum Commission

ONGC Oil and National Gas Corporation

ORA Oil Revenue Agreement

PA Petroleum Act 2012

PSA Production Sharing Agreement

SPLA Sudan Peoples Liberation Army

TFA Transitional Financial Arrangement

Abstract

The research explores the issue of oil sharing and production agreements in the secession of South Sudan from the Republic of Sudan. Despite equitable revenue sharing agreements embedded within the 2005 peace agreement between the two countries, many components of these agreements were never put into effect and discrepancies in figures published by the oil companies in the region and the Khartoum government have been uncovered. Explanations offered by the oil companies and the Khartoum government for such discrepancies fail to stand up to scrutiny and have never been backed by evidential data. Post secession of 2011, the Republic of Sudan faces a great loss in proven oil reserves and associated petrodollars; yet it retains the pipelines and refineries in the North and for the time being South Sudan is dependent upon these. It will be argued that secession in Sudan is not doomed, but is in fact the best chance for South Sudan to achieve an equitable share in the regions oil revenues; this situation does however rely upon an improved transparency on the part of both governments.

1.0 Introduction

This study will examine the role of oil and oil agreements in the secession of South Sudan from the Republic of South Sudan. In particular, it will consider the role of oil initially in the civil war, which ended in 2005 with the comprehensive peace agreement (CPA). The terms of this agreement were never fully implemented and many challenges between the two Sudans remain; which maintains the risk of future violence. The CPA required that oil revenues from oil produced in South Sudan be shared equally between North and South; however, evidence suggests that the North took far more than its fair share, deducting funds for election preparations and administrative functions. The lack of transparency on the part of the Khartoum government is exacerbated by the fact that the Southern government had no means of independently verifying anomalies in oil revenue reporting. It will be argued that there is a causal link between inequities in oil revenue sharing and the secession of South Sudan.

On 7 February 2011, the South Sudan Referendum Commission announced that the people of South Sudan had overwhelmingly voted in favour of independence in a referendum to exercise their right to self-determination.1 This vote was embedded within the 2005 CPA.2 Sudans civil war was the longest running war in Africa, engulfing almost the entire history of postcolonial Sudan until the conclusion of the CPA in 2005.3 Despite the fact that South Sudan is an oil-rich nation, it is also one of the least-developed regions on earth, although the country is rich in oil, the distribution of wealth has tended to be concentrated in Khartoum and the Nile valley at the expense of the peripheries of the country.4 Ninety per cent of people in the South, and fifty per cent in the North live on less than a dollar a day.5

For the people of the South therefore, although the majority of the country’s natural oil resources are territorially situated within their borders, the Khartoum government took control over the export and management of these resources within its own region. It would not be too difficult to appreciate that the people of the South may wish to seek the means to regain control of the oil revenues from resources mined within their own territory. The possibility will be explored within the foregoing discussion that the desire for independence of the South was at least in part motivated by the country’s distribution of oil and the wish for the equitable distribution of oil revenues.

2.0 Methodology

The research methodology is a secondary analysis of data, which has a number of advantages; in particular, it enables the researcher to allocate more time to the evaluation and interpretation of information.6 In the chosen area of research, which is an analysis of the impact of oil agreements in the secession of South Sudan, it would be difficult to conduct primary research within the appropriate timeframe. Oil industry reports, news media reports, academic journal articles and academic books will all be considered.

3.0 Results/Findings

3.1 Background

Despite the 2005 CPA, ethnic tensions and problematic relations with North Sudan maintained a constant risk of further escalating violence and return to civil war. The union between the South and the Republic of Sudan has been considered forced and disastrous.7 Secession also means a real risk of loss of oil revenue for the North; this has been estimated at as much as a possible 80 percent of Sudans proven oil reserves and associate petrodollars.8

Publically the issue that split the two Sudanese sides during the North-South Civil war was a campaign to convert the southern population to Islam; however, oil played a significant, if not dominant, role.9 Oil reserves in the Sudan are located primarily in Unity and Abyei provinces, which are in the South, but close to the border with the Northern part. When it became clear that Sudan might be sitting on major oil supplies, the North reasserted control and created a new province - Benititu - that primarily constituted of the country’s existing oilfields. In order to preserve security of supply, the Sudanese government decided to locate the countrys only oil refinery near Khartoum, over 1,000 km away, and build a pipeline from the oilfields to the refinery. This investment allowed the North to control the oil reserves and China supplied the technical expertise and financial investments to develop these reserves.10

The economy of South Sudan was previously based primarily on subsistence agriculture; it is now highly dependent upon oil. It is estimated that around 75% of the oil reserves in Sudan are in the area, which has recently gained independence.11 During the last 20 years, the Sudan has become an oil exporting country.12 The 2005 CPA provided South Sudan with 50% of the former united Sudans oil revenues, this provides for the vast majority of the countrys GDP; however, it is unlikely that South Sudan ever received this share.13

After independence, this agreement required renegotiation, but by January 2012, after a breakdown of talks, South Sudan halted oil production.14 The two Sudan countries agreed to resume pumping oil in March 2013, with a demilitarised buffer zone being set up in order to improve security. During the shutdown of oil production, South Sudans economy collapsed and vital development work placed on hold.15 The IMF estimated that the Republic of Sudans economy had shrunk by 11% in 2012 due to the loss of oil revenues.16

Figure 1: Sudan with oil pipelines, refineries and oil producing areas17

3.2 Oil Issues in Secession Negotiations

The newly independent South Sudan enjoys a certain degree of autonomy by having its own legislature, security forces and control over government revenues. The separation of the two regions should have brought an increase in oil revenues to the South, consequently lowering the profits of oil exploration in the North.18 However, the South possesses no infrastructure to sell its oil on the world market, as all of these are located in the North. South Sudan is extremely underdeveloped, with very few paved roads for trucks to carry oil, and there are no pipelines connecting its oilfields to other countries than those that run through the Republic of Sudan to Khartoum.19 This situation places the South in a position of weakness when it comes to negotiating around the issue of wealth sharing.

At present South Sudan is completely dependent on Port Sudan located in the North.20 The South has no choice but to lease the Northern oil pipeline, refineries and facilities at Port Sudan to sell its oil. Going forward, Southern officials propose the construction of an oil pipeline through Kenya to the Indian Ocean, which may prove more cost effective than paying the transport and refinery fees demanded by North Sudan.21 The President of the Republic of Sudan threatened not to allow South Sudan to use its infrastructure unless it paid $32 a barrel in August 2011, whereas South Sudan began negotiations by offering less than half a dollar per barrel.22 South Sudan later offered less than $5 a barrel, a figure that is much closer to average international rents.23

The ORA between the Republic of Sudan and South Sudan was reached on August 2012; it can be considered a preliminary agreement on oil-revenue sharing. The implementation of this agreement depends upon reaching further agreements on borders and other security issues.24 The ORA started when oil production recommenced on 24th March 201325 and covers a period of 3½ years. The ORA includes a TFA and pipeline related fees. The TFA agrees a payment of US$15 expressed in per barrel terms, based on South Sudans projection of an average of 150,000 barrels a day. If production is higher, payments will be made at this rate until cumulative payments have reached US$3,028 billion.26 Pipeline-related fees averaging US$9.7 a barrel were also negotiated for this 3½-year period; these fees will be renegotiated after the 3½-year period.27

In other perspectives, oil issues in Sudan secession negotiations are associated with oil corporations in Sudan. In Sudan, Multinational Oil Corporations (MNCs) involved in the poor country’s emergent petroleum industry became contentious issues in the Sudan civil war because of the unstable positioning of the nation’s oil fields.28 The conflict was mainly among succession factors. It is a consequence of continual financial and political disregard of the South by the northern regime both prior and after South Sudan independence.29 The issues of succession have existed mainly due to contested oil region in the border of North and South Sudan.

3.3 Discrepancies in oil revenue sharing

The aim of the CPA was a unified, pluralistic and democratic Sudan, which aimed to achieve a number of benchmarks for wealth sharing in the oil sector, improved governance, security and economic growth. The agreement also provided a mechanism for Southern Sudanese self-determination, if these elements were not achieved during the six-year interim period.30 South Sudan chose succession due to failed issues within the agreement, including North-South border demarcation, agreement of the Abyei protocol and inaccurate reporting of oil revenues by the North, meaning that the government of South Sudan has been unable to dispute whether it is receiving an accurate share of oil revenue.31 It is clear that lack of transparency on the part of the North and indications that the South was not receiving its fair share of the oil revenues, led to the eventual secession of the South.

Figure 2: Oil production companies

A 2009 Global Witness report states, "The oil figures published by the Khartoum government do not match those from other sources".32 In 2009, the oil companies operating in the Southern blocks reported a greater volume of oil production in these blocks than the government.33 These discrepancies range from 9%-26%, since the Southern government received $2.9 billion in oil revenues in 2009; if any underreporting by the Khartoum government were found, sums owed to the southern government would be considerable.34 Considering that the volume of oil reported by the Khartoum government in the only oil block that is located entirely in the North (block 6) is approximately the same as that reported by CNPC, the operator in the block,35 sheds even greater suspicion on Khartoums figures. At the same time, the Khartoum government deducted a three percent management fee from revenues shared with the South, which was difficult to justify since they already received half the revenue from the Southern wells.36

The CNPC established a major stake in Sudans oil productions, with the Multi-National Corporation being involved in multiple projects since the mid 1990s.37 CNPC, the Chinese oil company in the Sudan, faces little competition from Western multinationals. In Sudan, Chevron, for example left behind $2 billion of investments because of the Civil war.38 Conversely, China is of critical importance to the Sudan, since 80% of its oil exports went to China in 2012.39

Discrepancies in oil revenue sharing between Northern and Southern Sudan have been the source of conflict in the region. Oil discrepancies led to existing procedure of violence in an extended civil conflict in Sudan.40 The contesting issues surrounding Sudan’s oil hold vested economic interests in the persistence of violence.41 While civil conflict in Sudan has mainly been represented as a fight between Christians and Muslims or Africans and Arabs, economic causes for conflict has become increasingly evident with latest enlightenment surrounding the nation’s oil reserves.42 Consequently, grievances emerged within settled people and vengeance exhibited during the violence. The outline of conflict in Sudan shows that resource exhaustion and economic suppression were causes of conflict, not just supplementary outcomes.43

The discrepancy in oil sharing was evident in Northern Sudanese president when was interviewed. The interview took place a day following South Sudans self-government.44 He added that Abyei is component of Sudan and can only unite the south through the endorsement of nomadic Arab communities in a referendum, an improbable scenario.45 The Qatari TV, Al-Jazeera, documented that the country not only faces tensions with the North, but within its boundaries.46 These discrepancies can be associated with secessions that have doomed the republic of Sudan.

Research has shown that CPA did not put requirements on a post-independence oil sharing policies or transit cost.47 Consequently, after the secession, Sudan’s regime in Khartoum requested for transit costs of approximately $32-36 per barrel (bbl). However, South Sudan contradicted with below $1/bbl, which is coincidental with global principles.48 Given the different stands on transit fees and other self-governance issues, it is indistinct when South Sudan will resume oil production.49

3.4 Explanations of oil production discrepancies

There are three main foreign oil companies working in Sudan: CNPC, Petronas and the ONGC.50 In 2005, the volume of oil that the Khartoum government stated was produced in blocks 1, 2, 4 and 6 was 26% less than the company operating in these blocks, CNPC.51 The volume of oil that the Khartoum government stated was produced in blocks 3 and 7 in 2007 was 14% less than that stated in the annual report of the company operating in these blocks, CNPC.52 The Khartoum government and CNPC in 2011 explained these discrepancies. However, none of these arguments stands up to scrutiny, nor has either party provided any data that can substantiate their claims.53 Sudan oil is produced almost completely for export, this move distort investment, and let the nation’s economy susceptible to global product price fluctuations.54 Sudan dependence on oil has fueled the conflict.55

The main explanation offered by the Khartoum government is that the CNPCs production figures consist of oil that is mixed with water, whereas government figures are oil only. Further examination of this statement suggests that it is unlikely to be true, for it would imply that CNPC are publishing figures, which are also misleading to its shareholders and its customers, oil industry analysts have confirmed this fact.56 CNPC also offered an equally implausible explanation for the discrepancies; they suggested the discrepancy arose from the fact that oil production volumes were measured both in the oil field and at the final point of export.57 Their estimates suggested that a company might lose between 5 and 15% of oil between these 2 points of measurement, although such loses, appear highly inefficient. Moreover, this 5-15% loss could not account for the 26% discrepancy described earlier. A 10% loss in monetary terms would mean total lost revenues to the Khartoum government and the South Sudan government of $500 million in 2010 alone.58 If this were the case, serious questions would need to be asked about the oil industry’s transportation mechanisms in Sudan. The Sudanese government did not offer any explanation as to why government and oil production for block 6 (the only block entirely within North Sudan) match each other.59

Anomalies between the Khartoum government figures and those of CNPC have therefore fuelled serious mistrust in the share of oil revenues afforded to South Sudan pre-secession and provided an equitable share based on agreements embedded within the CPA. Post secession, a new regime of transparency has been introduced into South Sudans petroleum regime, which provides hope for a more prosperous future for the Republic of South Sudan.

Oil in Sudan brought another separating issue in two nation’s politics. Upon recognition of the importance of oil productions in southern Sudan, the Government of Sudan (GoS) changed regulations covering ownership of the nation’s oil capital by instituting novel northern country in southern terrain so that local authorities excluded from prospect revenues. This statement supports the assertion that secession of the republic of South Sudan came from republic of Sudan doom. It is mystifying to examine such a result.60

Another oil production discrepancy associated with secession is about oil production firms and procedures. Sudan had a potential oil industry and the overseas corporation had the first-mover benefit, acquired by seizing the rights to the mainstream of oil dispensations. The company’s technique of departure presents further questions.61

3.5 Overview of Petroleum Regime in the Republic of South Sudan

One does not need to be entirely pessimistic about the secession of South Sudan; a new petroleum regime has been established since secession. These commitments are enshrined within the Transitional Constitution, South Sudans PA 2012 and in draft Petroleum Revenue Management Bill, 2012. These articles are sets out a clear blueprint for how oil operations, contracts and revenues should be managed.62 The PA 2012 includes many important provisions aimed at preventing corruption and mismanagement within the oil industry. The draft Petroleum Revenue Management Bill, 2012 includes specifications on how revenues will be collected, managed, audited, and reported.63

Implementation of the provisions is key to transparency within South Sudans oil sector. As a minimum, the South Sudanese government is now legally bound to publish regular, detailed production and financial data, and all oil sector contracts, establish a single petroleum account, and provide oversight mechanisms for the management of oil contracts and revenues.64 Many of these provisions aim to combat the existence of corruption within South Sudan, which it is estimated cost the government more than US$4 billion between 2006 and 2012.65

It has been noted that the PA 2012 contains a potentially dangerous loophole, in its provision of confidentiality clauses. It provides that information can be withheld from the public if it contains proprietary data or if it threatens the climate of competition.66 The draft Petroleum Revenue Management Bill, 2012 also contains a confidentiality clause; this time it is accompanied by specific limitations, time expiration and for the rational for the enforcement of the confidentiality to be made available on request.67

Petroleum regime dominance is associated with the governance policies. The rising supremacy of the Eastern-oriented MNCs has been a characteristic trait of the Sudanese oil production in latest years. Since the departure of Western-oriented oil firms, the three regime-owned firms have recognized stable and increasing levels of oil production and led exploration movement.68 The inspirations of Eastern MNCs are mainly a blend of the craving to achieve global oil reserves and gain acquaintance on oil discovery and production. However, in spite of the ostensibly terrifying control, these corporations have in the Sudanese oil production; exterior issues have limited the extents of their accomplishments.69

The secession could also be tied to sustain government against opposition and fuel corruption. Similarly, a non-liberal regime’s need to share economic benefits generally in order to sustain social arrangement may be minimized by revenue streams coming from oil extraction. It can be applied to strengthen the state’s armed capacity and bribe the resistance. Likewise, possessions can be directed from government coffers to personal bank accounts through dishonest officials in non-honest regimes.70

4.0 Conclusion

It has been suggested that ensuring Sudans oil revenues are shared fairly between North and South in post secession Sudan is as critical as ever in preventing a return to civil war between the neighbours. It seems clear that inequitable dealings on the part of the Republic of Sudan in terms of revenue sharing have led to an atmosphere of distrust of the North; secession was the culmination of the failure of the CPA and unimplemented provisions therein. Is secession doomed? Secession it seems is South Sudans only hope for an equitable share in the revenue from the natural resources belonging to the people of South Sudan; distrust between north and south is enduring and separation appears to be South Sudans best chance for future prosperity.

Reference List

Legislation

Secondary sources

Ministry of Justice, 2012. Petroleum Revenue Management Bill, 2012. Laws of South Sudan (draft). Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.globalwitness.org/sites/default/files/library/Republic%20of%20South%20Sudan,%20draft%20Petroleum%20Revenue%20Management%20Bill,%202012_0.pdf

The Petroleum Act, 2012, Laws of South Sudan. Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.southsudanankara.org/docs/The%20Petroleum%20Act%202012.pdf

Books

Bryman, A 2012, Social Research Methods, (4th Edition), Oxford University Press.

Collier. P & Sambanis, N 2005, Understanding Civil War: Evidence and Analysis. (Eds.). The World Bank.

Lee, H & Shalmon, D 2008, “Searching for Oil: Chinas Oil Strategies in Africa” Robert I. Rotberg(Ed), China into Africa: Trade, Aid and Influence. Brookings Institution Press 109-136

Articles

ECOS 2011, European Coalition of Oil in Sudan, Sudans Oil Industry after the Referendum, Conference Report.

Energy Information Administration 2012, Sudan and South Sudan. Country Analysis Briefs. 1-8.

Global Witness 2009, Fuelling Mistrust: The Need for Transparency in Sudans Oil Industry.

Global Witness 2011, Crude Calculations: The Continues Lack of Transparency over Oil in Sudan.

Global Witness, 2012a, Blueprint for Prosperity: How South Sudans New Laws Hold the Key to a Transparent and Accountable Oil Sector (Global Witness Limited)

Mehler, A., Melber, H. and Van Walraven, K.2012, Politics, Economy and Society of South of the Sahara. Africa Yearbook Vol. 9: Brill

Patey, LA 2006, A Complex Reality: The Strategic Behaviour of Multinational Oil Corporations and the New Wars in Sudan Danish Institution for International Studies DIIS REPORT.

Shafaeddin, M. Oil and Challenges of Trade Policy Making In Sudan in a Globalizing Arena, Conference Paper for " Opportunities and Challenges of Development for Africa in the Global Arena”Addis Ababa, 15-17 November 2007

Sheeran, S.P. International Law, Peace Agreements and Self-Determination: the Case of the Sudan (2011) 60(2), International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 423-458

Switzer, J 2002, Oil and Violence in Sudan. International Institute for Sustainable Development.

Tadesse, D 2012, Post-Independence South Sudan: The Challenges Ahead, ISPI Working Paper, No.46.

Verhoeven, H & Patey, LA 2011, Sudans Islamists and the Post-Oil Era: Washingtons Role after Southern Secession. Middle East Policy Council vol. 18, issue 3: 1-9.

Young, J 2007, Emerging North-South Tensions and Prospects for a Return to War Small Arms Survey.

Online

Adkins, T 2011, The Politics of Oil and Secession in Sudan. Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://goxi.org/profiles/blogs/the-politics-of-oil-and?xg_source=activity

BBC 2011, South Sudan Backs Independence - Results BBC News Africa. Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-12379431.

BBC 2013, ‘Sudan Rivals to Resume Pumping Oil BBC News Africa, Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-21751896.

BBC 2015, South Sudan Profile BBC News Africa. Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-14069082.

Energy Information Administration 2014, Sudan and South Sudan, Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.eia.gov/countries/cab.cfm?fips=su

Global Witness 2012b, ‘Rigged: The Scramble for Africa’s Oil, Gas and Minerals,’ Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.globalwitness.org/rigged/rigged.pdf

International Monetary Fund 2012, Article IV Consultation, IMF Country Report No. 12/198 Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2012/cr12298.pdf

International Monetary Fund 2013, Sudan and the IMF Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.imf.org/external/country/sdn/index.htm

Mahjar-Barducci, A 2011, “The Precarious Birth of South Sudan” Gatestone Institute International Policy Council. Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/2264/south-sudan-birth

United Nations Development Programme 2012, The Milllennium Development Goals in South Sudan Eight Goals for 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.undp.org/content/south_sudan/en/home/mdgoverview/overview.html

Read

More

CHECK THESE SAMPLES OF Was the Secession of the Republic of South Sudan from the Republic of Sudan Doomed

Effectiveness of Humanitarian Intervention

Various different definitions have been presented by scholars from different schools of thought.... The paper "Effectiveness of Humanitarian Intervention" discusses that the use of military force in the form of humanitarian intervention and peacekeeping operations can only be said to be effective if the objectives of provision of fundamental human rights and sustained stability are achieved....

9 Pages

(2250 words)

Essay

New Imperialism in Africa

Under Muhammad Ali, Egypt's founder, Egypt was led into invasions of sudan, Arabia, Greece, Syria and Anatolia from 1805-1848.... 'The Wars of sudan: From Egyptian Conquest to the Present'.... n 1875 and 1877, with Egypt's control of sudan, Sudan became involved with Egypt's retaliation when Ethiopia attempted to take control of the coastal area of the Red Sea.... The paper "New Imperialism in Africa" highlights that today sudan is consumed by the ravages of its colonial experiences....

11 Pages

(2750 words)

Essay

Ethnic Violence in Darfur and International Response

Civil War, slavery, and torture have plagued the Islamic country of sudan for more than 50 years.... hile sudan is a member state to the United Nations Charter, whose purpose is to prevent atrocities such as the Holocaust from reoccurring, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to which the sudan is a signatory is incapable of enforcement absent consent to international jurisdiction.... istory of Violence sudan is the largest country in Africa....

35 Pages

(8750 words)

Essay

The Watergate Scandal

The men were discovered to be affiliated to the republic Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP).... In 1972, Republican officers broke into Democratic head offices at the Watergate Building Complex.... After the incident, investigators found burglary devices, cameras, telephone-tapping equipment, and a large amount of....

15 Pages

(3750 words)

Research Paper

Fight Against Colonialism

The south was left to be run by local chieftains with no involvement from the central government.... During the colonization of Africa sudan was an object of colonization by the Belgians, French and the British.... A joint British and Egyptian invasion finally defeated the Sudanese and sudan became a joint colony of both Egypt and Britain under the Condominium arrangement.... After Egypt attained its independence sudan was divided between those who wanted sudan to become part of Egypt and those who wanted independence and the former prevailed....

45 Pages

(11250 words)

Term Paper

Womens Rights in the USA Versus South Africa

ook contends that as a general principle, States have either failed to or refused to accept the human rights violations that are being suffered by some individuals simply because they are female and the problems they suffer from, such as rape or intimate partner violence are considered to belong to a private realm where the law has no right to interfere.... This study, Women's Rights in the USA Versus south Africa, stresses that gender inequality is one of the problems that are still prevalent throughout the world, although it may be comparatively worse in developing countries as compared to the developed countries....

18 Pages

(4500 words)

Research Paper

Illegal Trading of Raw Materials and Civil Conflict in Africa

After its independence from Portugal in 1974, Angola since then had been besieged by an atrocious and long civil war.... This paper attempts to see the correlation between civil conflict and raw materials illegally trade.... As such, the primary question that this paper intends to address is 'How the illegal trading of raw materials contributes to civil conflicts in Africa?...

14 Pages

(3500 words)

Research Paper

Catalan Language

from the Romance languages group, the Catalan language came into existence during the time period of 8th and 10th Centuries on either side of Pyrenees, in the regions of Carolingian Empire that gave birth to the counties of Spanish March.... The 12th and 13th centuries marked the spread of Catalan Language from southwards to eastwards with conquests of Catalan Aragonese Crown, and also the linguistic border was established in Jaume 1st reign.... It is a language that is derived from neo-Latin languages such as Italian, Spanish, French, Rumanian, and Portuguese....

9 Pages

(2250 words)

Research Proposal

sponsored ads

Save Your Time for More Important Things

Let us write or edit the research paper on your topic

"Was the Secession of the Republic of South Sudan from the Republic of Sudan Doomed"

with a personal 20% discount.

GRAB THE BEST PAPER

✕

- TERMS & CONDITIONS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- COOKIES POLICY